1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Copenhagen

COPENHAGEN (Danish Kjöbenhavn), the capital of the kingdom of Denmark, on the east coast of the island of Zealand (Sjaelland) at the southern end of the Sound. Pop. (1901) 400,575. The latitude is approximately that of Moscow, Berwick-on-Tweed and Hopedale in Labrador. The nucleus of the city is built on low-lying ground on the east coast of the island of Zealand, between the sea and a series of small freshwater lakes, known respectively as St Jörgens Sö, Peblings Sö and Sortedams Sö, a southern portion occupying the northern part of the island of Amager. An excellent harbour is furnished by the natural channel between the two islands; and communication from one division to the other is afforded by two bridges—the Langebro and the Knippelsbro, which replaced the wooden drawbridge built by Christian IV. in 1620. The older city, including both the Zealand and Amager portions, was formerly surrounded by a complete line of ramparts and moats; but pleasant boulevards and gardens now occupy the westward or landward site of fortifications. Outside the lines of the original city (about 5 m. in circuit), there are extensive suburbs, especially on the Zealand side (Österbro, Nörrebro and Vesterbro or Österfölled, &c., and Frederiksberg), and Amagerbro to the south of Christianshavn.

The area occupied by the inner city is known as Gammelsholm (old island). The main artery is the Gothersgade, running from Kongens Nytorv to the western boulevards, and separating a district of regular thoroughfares and rectangular blocks to the north from one of irregular, narrow and picturesque streets to the south. The Kongens Nytorv, the focus of the life of the city and the centre of road communications, is an irregular open space at the head of a narrow arm of the harbour (Nyhavn) inland from the steamer quays, with an equestrian statue of Christian V. (d. 1699) in the centre. The statue is familiarly known as Hesten (the horse) and is surrounded by noteworthy buildings. The Palace of Charlottenborg, on the east side, which takes its name from Charlotte, the wife of Christian V., is a huge sombre building, built in 1672. Frederick V. made a grant of it to the Academy of Arts, which holds its annual exhibition of paintings and sculpture in April and May, in the adjacent Kunstudstilling (1883). On the south is the principal theatre, the Royal, a beautiful modern Renaissance building (1874), on the site of a former theatre of the same name, which dated from 1748. Statues of the poets Ludvig Holberg (d. 1754), and Adam Öhlenschläger (d. 1850), the former by Stein and the latter by H. V. Bissen, stand on either side of the entrance, and the front is crowned by a group by King, representing Apollo and Pegasus, and the Fountain of Hippocrene. Within, among other sculptures, is a relief figure of Ophelia, executed by Sarah Bernhardt. Other buildings in Kongens Nytorv are the foreign office, several great commercial houses, the commercial bank, and the Thotts Palais of c. 1685. The quays of the Nyhavn are lined with old gabled houses.

From the south end of Kongens Nytorv, a street called Holmens Kanal winds past the National Bank to the Holmens Kirke, or church for the royal navy, originally erected as an anchor-smithy by Frederick II., but consecrated by Christian IV., with a chapel containing the tombs of the great admirals Niels Juel and Peder Tordenskjöld, and wood-carving of the 17th century. The street then crosses a bridge on to the Slottsholm, an island divided from the mainland by a narrow arm of the harbour, occupied mainly by the Christiansborg and adjacent buildings. The royal palace of Christiansborg, originally built (1731–1745) by Christian VI., destroyed by fire in 1794, and rebuilt, again fell in flames in 1884. Fortunately most of the art treasures which the palace contained were saved. A decision was arrived at in 1903, in commemoration of the jubilee of the reign of Christian IX., to rebuild the palace for use on occasions of state, and to house the parliament. On the Slottsplads (Palace Square) which faces east, is an equestrian statue of Frederick VII. There are also preserved the bronze statues which stood over the portal of the palace before the fire—figures of Strength, Wisdom, Health and Justice, designed by Thorvaldsen. The palace chapel, adorned with works by Thorvaldsen and Bissen, was preserved from the fire, as was the royal library of about 540,000 volumes and 20,000 manuscripts, for which a new building in Christiansgade was designed about 1900.

The exchange (Börsen), on the quay to the east, is an ornate gabled building erected in 1619–1640, surmounted by a remarkable spire, formed of four dragons, with their heads directed to the four points of the compass, and their bodies entwining each other till their tails come to a point at the top. To the south is the arsenal (Töjhus) with a collection of ancient armour.

The Thorvaldsen museum (1839–1848), a sombre building in a combination of the Egyptian and Etruscan styles, consists of two storeys. In the centre is an open court, containing the artist’s tomb. The exterior walls are decorated with groups of figures of coloured stucco, illustrative of events connected with Thorvaldsen’s life. Over the principal entrance is the chariot of Victory drawn by four horses, executed in bronze from a model by Bissen. The front hall, corridors and apartments are painted in the Pompeian style, with brilliant colours

and with great artistic skill. The museum contains about 300  |

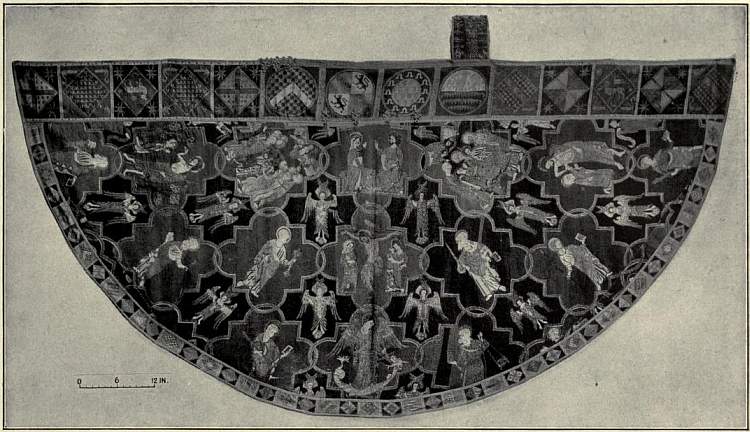

| Fig. 2.—THE SYON COPE. (English, 13th Century.) |

The medallions with which it is embroidered contain representations of Christ on the Cross, Christ and St Mary Magdalene, Christ and Thomas, the death of the Virgin, the burial and coronation of the Virgin, St Michael and the twelve Apostles. Of the latter, four survive only in tiny fragments. The spaces between the four rows of medallions are filled with six-winged cherubim. The ground-work of the vestment is green silk embroidery, that of the medallions red. The figures are worked in silver and gold thread and coloured silks. The lower border and the orphrey with coats of arms do not belong to the original cope and are of somewhat later date. The cope belonged to the convent of Syon near Isleworth, was taken to Portugal at the Reformation, brought back early in the 19th century to England by exiled nuns and given by them to the Earl of Shrewsbury. In 1864 it was bought by the South Kensington Museum.

|

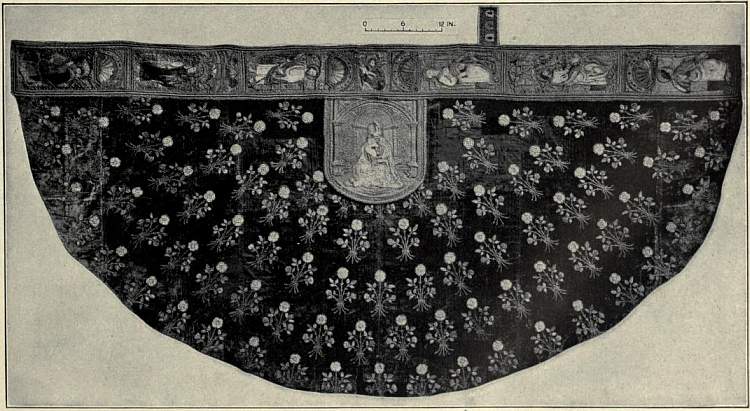

| Fig. 3.—COPE OF BLUE SILK VELVET, WITH APPLIQUÉ WORK AND EMBROIDERY. |

In the middle of the orphrey is a figure of Our Lord holding the orb in His left hand and with His right hand raised in benediction. To the right are figures of St Peter, St Bartholomew and St Ursula; and to the left, St Paul, St John the Evangelist and St Andrew. On the hood is a seated figure of the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Saviour. German: early 16th century. (In the Victoria and Albert Museum, No. 91. 1904.)

of Thorvaldsen’s works; and in one apartment is his sitting-room furniture arranged as it was found at the time of his death in 1844.

On the mainland, immediately west of the Slottsholm, is the Prinsens Palais, once the residence of Christian V. and Frederick VI. when crown princes, containing the national museum. This consists of four sections, the Danish, ethnographical, antique and numismatic. It was founded in 1807 by Professor Nyerup, and extended between 1815 and 1885 by C. J. Thomsen and J. J. A. Worsaae, and the ethnographical collection is among the finest in the world. From this point the Raadhusgade leads north-west to the combined Nytorv-og-Gammeltorv, where is the old townhall (Raadhus, 1815), and continues as the Nörregade to the Vor Frue Kirke (Church of our Lady), the cathedral church of Copenhagen. This church, the site of which has been similarly occupied since the 12th century, was almost entirely destroyed in the bombardment of 1807, but was completely restored in 1811–1829. The works of Thorvaldsen which it contains constitute its chief attraction. In the pediment is a group of sixteen figures by Thorvaldsen, representing John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness; over the entrance within the portico is a bas-relief of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem; on one side of the entrance is a statue of Moses by Bissen, and on the other a statue of David by Jerichau. In a niche behind the altar stands a colossal marble statue of Christ, and marble statues of the twelve apostles adorn both sides of the church.

Immediately north of Vor Frue Kirke is the university, founded by Christian I. in 1479; though its existing constitution dates from 1788. The building dates from 1836. There are five faculties—theological, juridical, medical, philosophical and mathematical. In 1851 an English and in 1852 an Anglo-Saxon lectureship were established. All the professors are bound to give a series of lectures open to the public free of charge. The university possesses considerable endowments and has several foundations for the assistance of poor students; the “regent’s charity,” for instance, founded by Christian, affords free residence and a small allowance to one hundred bursars. There are about 2000 students. In connexion with the university are the observatory, the chemical laboratory in Ny Vester Gade, the surgical academy in Bredgade, founded in 1786, and the botanic garden. The university library, incorporated with the former Classen library, collected by the famous merchants of that name, contains about 200,000 volumes, besides about 4000 manuscripts, which include Rask’s valuable Oriental collection and the Arne-Magnean series of Scandinavian documents. It shares with the royal library the right of receiving a copy of every book published in Denmark. There is also a zoological museum. Adjacent is St Peter’s church, built in a quasi-Gothic style, with a spire 256 ft. high, and appropriated since 1585 as a parish church for the German residents in Copenhagen. A short distance along the Krystalgade is Trinity church. Its round tower is 111 ft. high, and is considered to be unique in Europe. It was constructed from a plan of Tycho Brahe’s favourite disciple Longomontanus, and was formerly used as an observatory. It is ascended by a broad inclined spiral way, up which Peter the Great is said to have driven in a carriage and four. From this church the Kjöbermayergade runs south, a populous street of shops, giving upon the Höibro-plads, with its fine equestrian statue of Bishop Absalon, the city’s founder. This square is connected by a bridge with the Slottsholm.

The quarter north-east of Kongens Nytorv and Gothersgaden is the richest in the city, including the palaces of Amalienborg, the castle and gardens of Rosenborg and several mansions of the nobility. The quarter extends to the strong moated citadel, which guards the harbour on the north-east. It is a regular polygon with five bastions, founded by Frederick III. about 1662–1663. One of the mansions, the Moltkes Palais, has a collection of Dutch paintings formed in the 18th century. This is in the principal thoroughfare of the quarter, Bredgaden, and close at hand the palace of King George of Greece faces the Frederikskirke or Marble church. This church, intended to have been an edifice of great extent and magnificence, was begun in the reign of Frederick V. (1749), but after twenty years was left unfinished. It remained a ruin until 1874, when it was purchased by a wealthy banker, M. Tietgen, at whose expense the work was resumed. The edifice was not carried up to the height originally intended, but the magnificent dome, which recalls the finest examples in Italy, is conspicuous far and wide. The diameter is only a few feet less than that of St Peter’s in Rome. As the church stands it is one of the principal works of the architect, F. Meldahl. Behind King George’s palace from the Bredgade lies the Amalienborg-plads, having in the centre an equestrian statue of Frederick V., erected in 1768 at the cost of the former Asiatic Company. The four palaces, of uniform design, encircling this plads, were built for the residence of four noble families; but on the destruction of Christiansborg in 1794 they became the residence of the king and court, and so continued till the death of Christian VIII. in 1848. One of the four is inhabited by the king, the second and third by the crown prince and other members of the royal family, while the fourth is occupied by the coronation and state rooms. The Ameliegade crosses the plads and, with the Bredgade, terminates at the esplanade outside the citadel, prolonged in the pleasant promenade of Lange Linie skirting the Sound.

To the west of the citadel is the Ostbanegaard, or eastern railway station, from which start the local trains on the coast line to Klampenborg and Helsingör. South-west from this point extends the line of gardens which occupy the site of former landward fortifications, pleasantly diversified by water and plantations, skirted on the inner side by three wide boulevards, Östervold, Nörrevold and Vestervold Gade, and containing noteworthy public buildings, mostly modern. In the Östre Anlaeg is the art museum (1895) containing pictures, sculptures and engravings. In front of it is the Denmark monument (1896), commemorating the golden wedding (1892) of Christian IX. and Queen Louisa. Among various scenes in relief, the marriage of King Edward VII. of England and Queen Alexandra is depicted. The botanical garden (1874) contains an observatory with a statue of Tycho Brahe, and the chemical laboratory, mineralogical museum, polytechnic academy (1829) and communal hospital adjoin it. On the inner side of Östevold Gade is Rosenborg Park, with the palace of Rosenborg erected in 1610–1617. It is an irregular building in Gothic style, with a high pointed roof, and flanked by four towers of unequal dimensions. It contains the chronological collection of Danish monarchs, including a coin and medal cabinet, a fine collection of Venetian glass, the famous silver drinking-horn of Oldenburg (1474), the regalia and other objects of interest as illustrating the history of Denmark. The Riddersal, a spacious room, is covered with tapestry representing the various battles of Christian V., and has at one end a massive silver throne. The Nörrevold Gade leads through the Nörretorv past the Folke-teatre and the technical school to the Örsteds park, and from its southern end the Vestervold Gade continues through the Raadhus Plads, a centre of tramways, flanked by the modern Renaissance town hall (1901), ornamented with bronze figures, with a tower at the eastern angle. Here is also the museum of industrial art, and the Ny-Carlsberg Glyptotek, with its collection of sculpture, is on this boulevard, which skirts the pleasure garden called Tivoli. From the Raadhus-plads the Vesterbro Gade runs towards the western quarter of the city, skirting the Tivoli. Here is the Dansk Folke museum, a collection illustrating the domestic life of the nation, particularly that of the peasantry since 1600. A column of Liberty (Friheds-Stötte) rises in an open space, erected in 1798 to commemorate the abolition of serfdom. Immediately north is the main railway station (Banegaard), and the North and Klampenborg stations near at hand. The western (residential) quarter contains the park of Frederiksberg, with its palace erected under Frederick IV. (d. 1730), used as a military school. The park contains a zoological garden, and is continued south in the pleasant Söndermarken, near which lies the old Glyptotek, which contained the splendid collection of sculptures, &c., made by H. C. Jacobsen since 1887, until their removal to the new Glyptotek founded by him in the Vestre Boulevard.

The quarter of Christianshavn is that portion of the city which skirts the harbour to the south, and lies within the fortifications. It contains the Vor Frelsers Kirke (Church of Our Saviour), dedicated in 1696, with a curious steeple 282 ft. high, ascended by an external spiral staircase. The lower part of the altar is composed of Italian marble, with a representation of Christ’s sufferings in the garden of Gethsemane; and the organ is considered the finest in Copenhagen. The city does not extend much farther south, though the Amagerbro quarter lies without the walls. The island of Amager is fertile, producing vegetables for the markets of the capital. It was peopled by a Dutch colony planted by Christian II. in 1516, and many old peculiarities of dress, manners and languages are retained.

The environs of Copenhagen to the north and west are interesting, and the country, both along the coast northward and inland westward is pleasant, though in no way remarkable. The railway along the coast northward passes the seaside resorts of Klampenborg (6 m.) and Skodsborg (10 m.). Near Klampenborg is the Dyrehave (Deer park) or Skoven (the forest), a beautiful forest of beeches. The Zealand Northern railway passes Lyngby, on the lake of the same name, a favourite summer residence, and Hilleröd (21 m.), a considerable town, capital of the amt (county) of Frederiksberg, and close to the palace of Frederiksberg. This was erected in 1602–1620 by Christian IV., embodying two towers of an earlier building, and partly occupying islands in a small lake. It suffered seriously from fire in 1859, but was carefully restored under the direction of F. Meldahl. It contains a national historical museum, including furniture and pictures. The palace church is an interesting medley of Gothic and Renaissance detail. The villa of Hvidöre was acquired by Queen Alexandra in 1907.

Among the literary and scientific associations of Copenhagen may be mentioned the Danish Royal Society, founded in 1742, for the advancement of the sciences of mathematics, astronomy, natural philosophy, &c., by the publication of papers and essays; the Royal Antiquarian Society, founded in 1825, for diffusing a knowledge of Northern and Icelandic archaeology; the Society for the Promotion of Danish Literature, for the publication of works chiefly connected with the history of Danish literature; the Natural Philosophy Society; the Royal Agricultural Society; the Danish Church History Society; the Industrial Association, founded in 1838; the Royal Geographical Society, established in 1876; and several musical and other societies. The Academy of Arts was founded by Frederick V. in 1754 for the instruction of artists, and for disseminating a taste for the fine arts among manufacturers and operatives. Attached to it are schools for the study of architecture, ornamental drawing and modelling. An Art Union was founded in 1826, and a musical conservatorium in 1870 under the direction of the composers N. W. Gade and J. P. E. Hartmann.

Among educational institutions, other than the university, may be mentioned the veterinary and agricultural college, established in 1773 and adopted by the state in 1776, the military academy and the school of navigation. Technical instruction is provided by the polytechnic school (1829), which is a state institution, and the school of the Technical Society, which, though a private foundation, enjoys public subvention. The schools which prepare for the university, &c., are nearly all private, but are all under the control of the state. Elementary instruction is mostly provided by the communal schools.

The churches already mentioned belong to the national Lutheran Church; the most important of those belonging to other denominations are the Reformed church, founded in 1688, and rebuilt in 1731, the Catholic church of St Ansgarius, consecrated in 1842, and the Jewish synagogue in Krystalgade, which dates from 1853. Of the monastic buildings of medieval Copenhagen various traces are preserved in the present nomenclature of the streets. The Franciscan establishment gives its name to the Graabrödretorv or Grey Friars’ market; and St Clara’s Monastery, the largest of all, which was founded by Queen Christina, is still commemorated by the Klareboder or Clara buildings, near the present post-office. The Duebrödre Kloster occupied the site of the hospital of the Holy Ghost.

Among the hospitals of Copenhagen, besides many modern institutions, there may be mentioned Frederick’s hospital, erected in 1752–1757 by Frederick V., the Communal Hospital, erected in 1859–1863, on the eastern side of the Sortedamssö, the general hospital in Ameliegade, founded in 1769, and the garrison hospital, in Rigensgade, established in 1816 by Frederick VI. After the cholera epidemic of 1853, which carried off more than 4000 of the inhabitants, the medical association built several ranges of workmen’s houses, and their example was followed by various private capitalists, among whom may be mentioned the Classen trustees, whose buildings occupy an open site on the western outskirts of the city.

Copenhagen is by far the most important commercial town in Denmark, and exemplifies the steady increase in the trade of the country. The harbour is mainly comprised in the narrow strait between the outer Sound and its inlet the Kalvebod or Kallebo Strand. The trading capabilities were aided by the construction in 1894 of the Frihavn (free port) at the northern extremity of the town, well supplied with warehouses and other conveniences. It is connected with the main railway station by means of a circular railway, while a short branch connects it with the ordinary custom-house quay. The commercial harbour is separated from the harbour for warships (Orlogshavn) by a barrier. The sea approaches are guarded by ten coast batteries besides the old citadel. The Middelgrund is a powerful defensive work completed in 1896 and most of the rest are modern. The landward defences of Copenhagen, it may be added, were left unprovided for after the Napoleonic wars until the patriotism of Danish women, who subscribed sufficient funds for the first fort, shamed parliament into granting the necessary money for others (1886–1895). Copenhagen is not an industrial town. The manufactures carried on are mostly only such as exist in every large town, and the export of manufactured goods is inconsiderable. The royal china factory is celebrated for models of Thorvaldsen’s works in biscuit china. The only very large establishment is one for the construction of iron steamers, engines, &c., but some factories have been erected within the area of the free port for the purpose of working up imported raw materials duty free.

History.—Copenhagen (i.e. Merchant’s Harbour, originally simply Havn, latinized as Hafnia) is first mentioned in history in 1043. It was then only a fishing village, and remained so until about the middle of the 12th century, when Valdemar I. presented that part of the island to Axel Hvide, renowned in Danish history as Absalon (q.v.), bishop of Roskilde, and afterwards archbishop of Lund. In 1167 this prelate erected a castle on the spot where the Christiansborg palace now stands, and the building was called after him Axel-huus. The settlement gradually became a great resort for merchants, and thus acquired the name which, in a corrupted form, it still bears, of Kaupmannahöfn, Kjöbmannshavn, or Portus Mercatorum as it is translated by Saxo Grammaticus. In 1186, Bishop Absalon bestowed the castle and village, with the lands of Amager, on the see of Roskilde; but, as the place grew in importance, the Danish kings became anxious to regain it, and in 1245 King Eric IV. drove out Bishop Niels Stigson. On the king’s death (1250), however, Bishop Jacob Erlandsen obtained the town, and, in 1254, gave to the burghers their first municipal privileges, which were confirmed by Pope Urban III. in 1286. In the charter of 1254, while there is mention of a communitas capable of making a compact with the bishop, there is nothing said of any trade or craft gilds. These are, indeed, expressly prohibited in the later charter of Bishop Johann Kvag (1294); and the distinctive character of the constitution of Copenhagen during the middle ages consisted in the absence of the free gild system, and the right of any burgher to pursue a craft under license from the Vogt (advocatus) of the overlord and the city authorities. Later on, gilds were established, in spite of the prohibition of the old charters; but they were strictly subordinate to the town authorities, who appointed their aldermen and suppressed them when they considered them useless or dangerous. The prosperity of Copenhagen was checked by an attack by the people of Lübeck in 1248, and by another on the part of Prince Jaromir of Rügen in 1259. In 1306 it managed to repel the Norwegians, but in 1362, and again in 1368, it was captured by the opponents of Valdemar Atterdag. In the following century a new enemy appeared in the Hanseatic league, which was jealous of its rivalry, but their invasion was frustrated by Queen Philippa. Various attempts were made by successive kings to obtain the town from the see of Roskilde, as the most suitable for the royal residence; but it was not till 1443 that the transference was finally effected and Copenhagen became the capital of the kingdom. From 1523 to 1524 it held out for Christian II. against Frederick I., who captured it at length and strengthened its defensive works; and it was only after a year’s siege that it yielded in 1536 to Christian III. From 1658 to 1660 it was unsuccessfully beleaguered by Charles Gustavus of Sweden; and in the following year it was rewarded by various privileges for its gallant defence. In 1660 it gave its name to the treaty which concluded the Swedish war of Frederick III. In 1700 it was bombarded by the united fleets of England, Holland and Sweden; in 1728 a conflagration destroyed 1640 houses and five churches; another in 1795 laid waste 943 houses, the church of St Nicolas, and the Raadhus. In 1801 the Danish fleet was destroyed in the roadstead by the English (see below, § Battle of Copenhagen); and in 1807 the city was bombarded by the British under Lord Cathcart, and saw the destruction of the university buildings, its principal church and numerous other edifices.

See O. Nielsen, Köbenhavns Historie oz Beskrivelse (Copenhagen, 1877–1892); C. Bruun and P. Munch, Köbenhavn, Skrilding af dets Historie, &c. (ibid. 1887–1901); Bering-Lüsberg, Köbenhavn i gamle Dage (ibid. 1898 et seq.). (O. J. R. H.)

Battle of Copenhagen

The formation of a league between the northern powers, Russia, Prussia, Denmark and Sweden, on the 16th of December 1800, nominally to protect neutral trade at sea from the enforcement by Great Britain of her belligerent claims, led to the despatch of a British fleet to the Baltic on the 12th of March 1801. It consisted of fifty-three sail in all, of which eighteen were of the line. Prussia possessed no fleet. The nominal strength of the Russian fleet was eighty-three sail of the line, of the Danish twenty-three, and of the Swedish eighteen. But this force was for the most part only on paper. Some of the Russian ships were at Archangel, others in the Mediterranean. Of those actually in the Baltic and fit to go to sea, twelve were at Reval shut in by the ice, and the others were at Kronstadt. The Swedes could equip only eleven of the line for sea, and Denmark only seven or eight. It is highly doubtful whether the three powers could have collected more than forty ships of the line—and they would have been hastily manned, destitute of experience, and without confidence. A rapid British attack would in any case forestall the concentration of these heterogeneous squadrons. The superior quality of the veteran British crews was more than enough to counterbalance a mere superiority in numbers. The command of the British fleet was given to Sir Hyde Parker, an amiable man of no energy and little ability. He had Nelson with him as second in command—then a junior admiral but without rival in capacity and in his hold on the confidence of the fleet. Parker’s orders were to give Denmark twenty-four hours in which to withdraw from the coalition, and on her refusal to destroy or neutralize her strength and then proceed against the Russians before the breaking up of the ice allowed the ships at Reval to join the squadron at Kronstadt.

On the 21st of March the British fleet, after a somewhat stormy passage, was at the entrance to the Sound. Nicholas Vansittart, afterwards Lord Bexley, the British diplomatic agent entrusted with the message to the Danish government, was landed, and left for Copenhagen. On the 23rd he returned with the refusal of the Danes. The British fleet then passed the Danish fort at Cronenburg, unhurt by its distant fire, and without being molested by the forts on the Swedish shore. Nelson urged immediate attack, and recommended, as an alternative, that part of the British fleet should watch the Danes while the remainder advanced up the Baltic to prevent the junction of the Russian Reval squadron with the ships in Kronstadt. Sir Hyde Parker was, however, unwilling to go up the Baltic with the Danes unsubdued behind him, or to divide his force. It was therefore resolved that an attack should be made on the Danish capital with the whole fleet in two divisions. Copenhagen lies on the east side of the island of Zealand; opposite it is the shoal known as the Middle Ground. To the east of the Middle Ground is another shoal known as Saltholm Flat, and there is a passage available for large ships between them. The main fortification of Copenhagen was the powerful Trekroner (Three Crown) battery at the northern end of the sea-front. Here the Danes had placed their strongest ships. The southern part of the city front was covered by hulks and gun-vessels or bomb-vessels. There were in all eighteen hulks or ships of the line in the Danish defence. To have made the attack from the northern end would in Nelson’s words have been “to take the bull by the horns.” He therefore proposed that he should be detached with ten sail of the line, and the frigates and small craft, to pass between the Middle Ground and Saltholm Flat, and assail the Danish line at the southern end while the remainder of the fleet engaged the Trekroner battery from the north. Sir Hyde Parker accepted his offer, and added two ships of the line to the ten asked for by Nelson.

During the nights of the 30th and 31st of March the channel between the Middle Ground and Saltholm Flat was sounded by the boats of the British fleet, the Danes making no attempt to interfere with them. On the 1st of April Nelson brought his ships through. He had transferred his flag from his own ship the “St George” (98) to the “Elephant” (74), commanded by Captain Foley, because the water was too shallow for a three-decker. On the morning of the 2nd of April the wind was fair from the south-east, and at 9.30 a.m. the British squadron weighed anchor, led by the “Amazon” frigate, commanded by Captain Riou, and began to pass along the front of the Danish line. The Danes could bring into action 375 guns in all. Their hulks and bomb-vessels were supported by batteries on Zealand; but, as the water is shallow for a long distance from the shore, these defences were too far off to render them effectual aid on the south end of their line. Nelson disposed of a greater number of guns, 1058 in all, but some did not come into action. The “Agamemnon” (64), commanded by Captain Fancourt, was unable to round the south point of the Middle Ground. The “Bellona” (74), commanded by Captain Thompson, and the “Russel” (74), commanded by Captain Cuming, ran ashore on the Middle Ground, but within range though at too great a distance for fully effective fire. Captain Thompson lost his leg in the battle. The other ships passed between the “Bellona” and “Russel” and the Danes. The leading British ship, the “Defiance” (74), carrying the flag of Rear-Admiral Graves, anchored just south of the Trekroner. As the wind was from the south-east Sir Hyde Parker was unable to make the proposed attack from the north. The place opposite the Danish fort which was to have been taken by him was occupied by Captain Riou and the frigates. The “Elephant” anchored almost in the middle of the line. Fire was opened about 10 a.m., and at 11.30 the action was at its height.

Until 1 o’clock there was no diminution of the Danish fire. Sir Hyde Parker, who saw the danger of Nelson’s position, became anxious, and sent his second, Captain Robert Waller Ottway, to him with a message authorizing him to retire if he thought fit. Before Ottway, who had to go in a row-boat, reached the “Elephant,” Sir Hyde Parker had reflected that it would be more magnanimous in him to take the responsibility of ordering the retreat. He therefore hoisted the signal of recall. It was a well-meant but ill-judged order. Nelson could only have retreated before the south-easterly wind by going past the Trekroner fort, where the passage is narrow, and the navigation difficult. He therefore disregarded the signal, and amused himself and the few officers about him by putting his glass to his blind eye and saying that he could not see it. The frigates opposite the Trekroner did retreat, Captain Riou being slain as they drew off.

At about 2.30 the fire from the Danish hulks had been much beaten down, but as their crews fell, fresh men were sent from the shore and the fire was resumed. Nelson astutely and legitimately seized the opportunity to open negotiations with the Danes. He sent a flag of truce carried by Sir F. Thesiger ashore to the crown prince of Denmark (then regent of the kingdom), to say that unless he was allowed to take possession of the hulks which had surrendered he would be compelled to burn them, a course which he deprecated on the ground of humanity and his tenderness of “the brothers of the English the Danes.” The crown prince, who was shaken by the spectacle of the battle, allowed himself to be drawn into a reply, and to be referred to Sir Hyde Parker. Fire was suspended by the Danes to allow of time to receive Sir Hyde Parker’s answer. Nelson with intelligent promptitude availed himself of the interval to withdraw his squadron past the Trekroner. The difficulty found in getting the ships out—one of them grounded—showed how disastrous an attempt to draw off under fire of the forts must have been.

The Danish government, which had entered the coalition largely from fear of Russia, was not prepared to make very great sacrifices, and now entered into negotiations for an armistice. It was the more ready to do so because it received news of the assassination of the tsar Paul, which had happened on the 24th of March. An armistice was made for fourteen weeks, which left the British fleet free to proceed up the Baltic. On the 12th of April, after lightening the three-deckers of their guns, the fleet passed over the shallows. But its presence had now lost all military significance. Sir Hyde Parker was assured by the Russian minister at Copenhagen that the new tsar Alexander I. would not continue the policy of hostility with England and alliance with France which had proved fatal to his father. The Swedes, who like the Danes had entered the coalition under pressure from Russia, did not send their ships to sea. The government of the new tsar was prepared for an arrangement with England. The date of the final settlement was in all probability delayed by the activity of Nelson, and his belief that a British fleet was the best negotiator in Europe. The British government learnt of the tsar’s death on the 15th of April. On the 17th it instructed Sir Hyde Parker to agree to a suspension of hostilities, and not to take active measures against Russia so long as the Reval squadron did not put to sea. On the 21st of April, having now received a full account of the battle at Copenhagen, it recalled Sir Hyde Parker, whose vacillating conduct and want of enterprise had become manifest. He received the news of his recall on the 5th of May. Nelson, to whom the command passed, at once put to sea, and hastened with a part of his fleet to Reval, which he reached on the 12th of May. The Russian squadron had, however, cut a passage through the ice in the harbour on the 3rd, and had sailed for Kronstadt. Nelson was received with formal civility by the Russian officers, with whom he exchanged visits. He wrote a letter to Mr Garlike, secretary of the British embassy at St Petersburg, saying that he had come with a small squadron as the best way of paying “the very highest compliment” to the tsar.

The Russian government, which not unnaturally wished to avoid any appearance of acting under dictation, and was now in no anxiety for the Reval squadron, treated his presence as a menace. On the 13th of May Count Pahlen answered in a most peremptory letter informing Nelson that negotiations would be suspended while he remained at Reval. This retort caused Nelson annoyance which he did not attempt to conceal, but he justly concluded that he had nothing further to do at Reval, and therefore returned down the Baltic. Nelson remained with the fleet till he was relieved at his own request, and was able to sail for England on the 18th of June. He gave a proof of his regard for the service of the country by taking his passage home in a small brig rather than withdraw a line of battle ship from the squadron, which his rank entitled him to do, and as other admirals of the time generally did. The British sailors and ships embargoed in Russia were released on the 17th of May. Great Britain released her prisoners on the 4th of June, and on the 17th of June was signed the convention which terminated the Baltic campaign.

See Dispatches and Letters of Vice-Admiral Nelson, by Sir N. Harris Nicolas (1845); Life of Nelson, by Capt. A. T. Mahan (London, 1899). (D. H.)